During the 1800s, the Victorians, inspired by Newton, became convinced of the fundamentally mechanical nature of the universe. The planets moved as exactly as the hands of a clock. Every star, every animal, every plant, and every human was a precisely milled gear in the mechanism of the universe. Each species filled its role perfectly and frictionlessly, as it was meant to. The Victorians rapidly began applying Newtonian principles everywhere.

An orrery, a Victorian era working model of the solar system.[Image source]

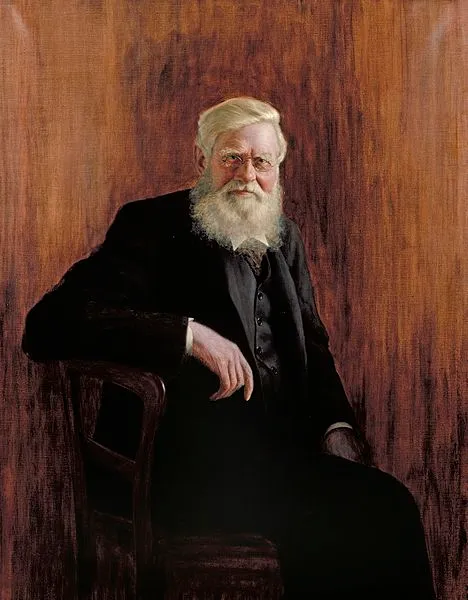

The noted Victorian biologist Alfred Russel Wallace gives us a great example of a mechanistic view of nature. He was best known for discovering evolution simultaneously with the older Charles Darwin, and then losing the credit when Darwin published first. (Darwin had the better grasp of the idea as well, though Wallace was certainly brilliant.) As a young man, Wallace traveled widely in South America. He said of the Amazon rainforest that "Every form of vegetation has become alike adapted to its genial heat and ample moisture, which has probably changed little even throughout geological periods". The whole Victorian idea of the Amazon was that it was a stable, unchanging gear in the clock.

Alfred Russel Wallace [Image source]

This worldview wasn't just limited to scientists, by any means. Almost every Victorian intellectual believed this, from the most devout Christian to the staunchest follower of Darwin. It didn't matter whether God or evolution had placed species where they were, it just mattered that they fit exactly, just as these ideas exactly fit the character of the time. It justified the social inequality rampant in the streets. It positioned mankind perfectly as the rightful ruler of nature. Victorian intellectual life offered every incentive to fall into this deterministic mode of thought. This was our best possible world, and everything and everyone belonged precisely where they were.

And they were completely wrong.

Newtonian physics works quite adequately for describing some basic orbital problems and the like. Physicists might gripe about it when it comes to relativity and quantum mechanics, but it's still perfectly fine to use for plenty of calculations. Unfortunately, it doesn't work at all when it comes to much of the rest of the universe. It's not a finely milled machine. We don't live in a deterministic universe.

Most people have probably at least heard about the fundamental unpredictability of the universe at a quantum scale, and that does interact with the macroscopic world (you've all heard the one about the cat in the box, right?), but that's not the only source of unpredictability in our universe. If you were to restart the universe, to run the whole experiment from the exact same starting point, it would always turn out different.

There's a few reasons for this, but it can, for the most part, be boiled down to emergent property. An emergent property is an unpredictable aspect of a system that arises from the interactions of simple, predictable parts. The study of emergent systems is an exceptionally complicated field, and we can't do it justice here, but it's worth discussing.

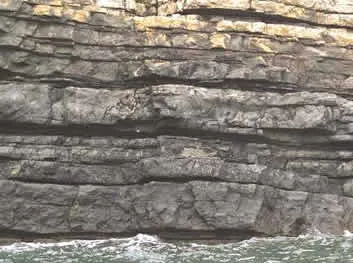

The Victorian model of the universe was one that fundamentally based in the idea that order is birthed from order, and gives rise to more order. In reality, most order is birthed from chaos. Turbidites are a fantastic example of this. Turbidites are a type of sedimentary rock. They're characterized by their incredibly even, tabular shape. They're one of the most orderly, clean-shaped rock deposits you'll ever find- and they're the deposits from the incredibly chaotic flows of underwater landslides. This is the result of a counterintuitive process- chaotic flow produces orderly, even deposits, while gentler, more orderly laminar flow produces jumbled, chaotic deposits.

A series of turbidite deposits. [Image source]

Why does a chaotic flow produce a more orderly deposit of sediment? Essentially, the flow mixes all the sediment it's carrying around, while a calmer flow just carries it along as it picked it up. Since it's unlikely that it was picked up in an orderly fashion, the sediment is unlikely to be deposited in an orderly fashion. In the turbulent flow, however, each particle of sediment is shaken and moved about, and the bigger grains are less affected by the currents than the smaller, resulting in the flow being arranged vertically by sediment size. Have you ever shaken a jar of rocks until the big ones end up on the bottom and the small ones on the top? It's the same principle.

Turbidites are far from the only orderly structures in nature produced by chaotic means. Crystals are grown in almost the same manner- the random movement of dissolved particles in the solution a crystal is grown in brings them together onto the crystal seed, producing the orderly internal structure of the crystal. Hurricanes are also emergent structures, as are the dendritic shapes many rivers take. This is very much a simplification of the concept, but it works well.

Treefall gaps illustrate another interesting way in in which nature defies Newtonian determinism. A treefall gap is when a tree or a large limb falls, clearing a hole in a forest from the canopy on down. It creates a new, abrupt change in the forest- an entirely new environment in which new saplings can grow, different animals flourish, and change in the forest occurs rapidly. In a diverse, healthy forest, there's absolutely no telling what will take root there- it's entirely unpredictable. This unpredictability is due to life's ability to react differently to different situations. There's no way to predict those reactions because there is no best adaptation- for any problem or new opportunity a species faces, there are countless different solutions to develop.

Looking up into a treefall gap. [Image source]

Remember talking about the Amazon a little while ago? It's by no means the unchanging, stable place that Wallace thought it was. It's no gear. It turns out that the extreme biodiversity of the Amazon rainforest comes from, essentially, tree gaps on an immense scale. During the last ice age, much of the world's water was locked up in the ice caps. This resulted in significantly lower rainfall in the Amazon. In response, the forest contracted against the rivers, leaving huge gaps of savannah-like environment between now-separate forests. The species resident in these places quickly began diverging evolutionarily. When the Ice Age ended and the forests reconnected, one species might find that it had become two, or three, or sixty.

To sum it all up: Nature builds order out of chaos, and it does so unpredictably when it comes to life due to life's ability to try different strategies. When you treat nature as predictable, you find that it becomes completely unpredictable. Now that we have started to treat nature as an unpredictable, chaotic, living thing, however, we're starting to be able to understand and predict it a little better.

Life is messy. Revel in it.

********************************

Bibliography:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergence

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treefall_gap

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_mechanics#Limits_of_validity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turbidite