I don't mean that Occam's Razor is just a little rusty- you pose a real risk of getting tetanus if you use it. For those unfamiliar with Occam's Razor, it's a proposition that states, in its most common form, that the simplest explanation is usually the correct one. And, not to dance around the topic, I can't stand the Razor.

William of Ockham, the English friar and philosopher (c 1287-1347) who the Razor is named after. His formulation of the idea was Numquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate (Plurality must never be posited without necessity). [Image source]

In its most popular form, the Razor is easy to lampoon. Plate tectonics is immensely more complex of an idea than its earlier alternatives, and yet it is, so far as we can tell, the correct answer. I can name literally dozens of other situations in which this is the case. This, however, is somewhat of a strawman attack upon the Razor- it can, and often is, phrased much more intelligibly than the popular version of it. A version of it with a stronger foundation is that "when presented with competing hypothetical answers to a problem, one should select the answer that makes the fewest assumptions." (Wikipedia's definition.) This clearly and apparently is more capable of withstanding a basic assault than the popular version.

Nonetheless, I still don't count myself a fan. There are a few reasons for that. One of them is the frequent interpretation of the history of science through its lens. Take the case of Copernicus, champion of the heliocentric (sun-centered), model of the solar system. Advocates of Occam's razor often point to the success of his model of the solar system over the older geocentric (Earth-centered) model of the solar system as a proving ground of the Razor. According to them, the geocentric model was by far the more complex one, requiring unnecessarily complex mathematical constructs called epicycles, extra little circular orbits tacked onto the main orbits. It's true that the geocentric model possessed epicycles, but guess what? So did the Copernican heliocentric model. In fact, it required 34 of them to function! This was because Copernicus predicted circular orbits for the planets, rather than elliptical ones. We don't know precisely how many epicycles the prior geocentric model used precisely, but there's no real evidence indicating that it used particularly more epicycles- nor, frankly, is the number of epicycles a greater complication than the sheer fact of their presence.

Nicolaus Copernicus, pioneer of the heliocentric model of the universe. [Image source]

Not only was Copernicus' explanation not simpler, but his detractors weren't actually doing bad science for the time. Their conclusions might have been incorrect by today's understanding, but they were actually doing their best to understand the universe using the evidence they had available to them. This is exemplified in the battles of Galileo Galilei, the heir to Copernicus' heliocentric torch. There's a common narrative that Galileo's main opponents were religious zealots in the Catholic Church, offended because he was defying what the Bible said. In actuality, however, his fiercest opponents were other astronomers, who rejected the heliocentric idea for strictly scientific reasons. (Specifically, the lack of an observed stellar parallax.) The whole Galileo getting house arrest for the latter part of his life thing? Well, his opponents basically sicced the Inquisition on him (science was really cutthroat back then). The Pope and the Jesuits, however, defended Galileo for years, only withdrawing their support when one of his books appeared to trash talk the Pope. Interestingly, Galileo rejected Kepler's heliocentric solution, which actually used ellipses and eliminated epicycles.

We could spend a whole book (and indeed many have) on the complex and weird nature of the Galileo situation, but getting back on topic, it's hardly the only example of the failure of even the better phrased version of Occam's Razor to explain events in the history of science. The rise of plate tectonics as a theory is, again, great to bring up. Not only is it not particularly simpler than its predecessors (though I should note that its predecessors tend to be far, far from simple- pre-tectonic explanations for mountain ranges were hellishly weird and complex at times), its adoption did, in fact, require the adoption of a huge amount of new assumptions, as seen by its opponents at the time. This is, in fact, a fairly common criticism of new scientific hypotheses. All scientific theories and hypotheses rest on a certain amount of assumptions, and for established theories, those assumptions tend to be pretty well supported. (The universe operates under the same laws of physics day-to-day is one pretty big assumption we all rely on, for instance.) New hypothesi, whether they're vindicated in the end or not, tend to rest on a great number of assumptions that have less support than the previously existing theories.

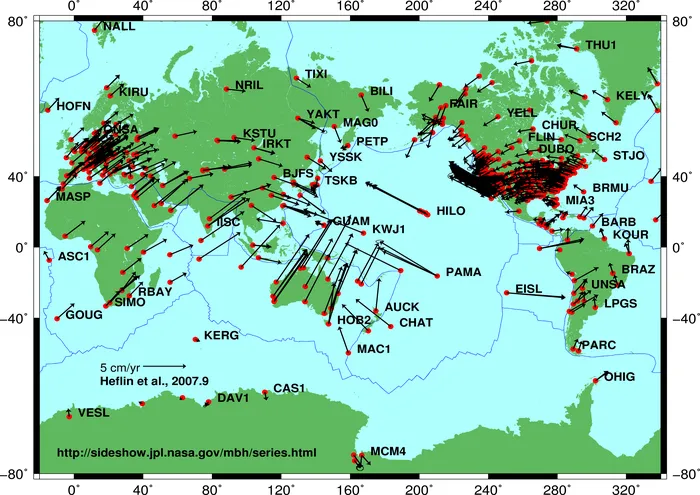

A map of Earth's known tectonic plates and their directions of movement. [Image source]

In fact, there's no point in the history of science that we can look at a battle between two rival theories and say that one won over the other thanks to it being the simpler one. Instead, the winner is the one that has more and better evidence backing its various assumptions and claims, as well as more accurate predictions- regardless of how many of each there are. Often, the number of claims that a hypothesis makes is enormous- but if they can all be backed with evidence, that can often lead it to victory against a simpler, more elegant answer. In this sense, Occam's Razor can be somewhat criticized as telling us to do less work to prove our ideas. That's clearly not an intended claim of the vast majority of its advocates and users, but it is an odd logical consequence of it.

Occam's Razor in the context of the history of science plays a very specific ideological role- that of reinforcing the image of us advancing from ignorance to enlightenment. While this is a true image in many senses, it has proceeded to the point of demonizing past theories as absurd, ignorant, and superstitious, along with their advocates. There's a lot of quite deliberate reasons to do so- they often are in place for the purpose of attacking religion. The idea that medieval people believed the Earth was flat, for example, was one of those. They very much didn't- they'd known the Earth was round since ancient Greek times. There are, in fact, only one or two references to a flat Earth we've found in medieval documents at all. This whole idea arose as propaganda during the Reformation, when Catholics and Protestants regularly began hurling it as an insult- only a fool would believe the Earth was flat, so if the other side believed that, then they were fools! It was then adopted and treated as true by a number of historians unfriendly to religion in the late 1800s, and has been passed down to a great number of people today, like the angry atheist movement. It's also become part of the mythology around Christopher Columbus, that he knew the Earth was round when his opponents doubted it. Actually, everyone involved knew the Earth was round, Columbus just thought the Earth was way smaller than everyone else, and they were worried he'd die in a giant empty ocean from lack of food and water before he reached Asia. Unfortunately, this narrative of medieval people thinking the Earth is flat has also been used as evidence that the Earth actually is flat by Flat Earthers, which is ironic on quite a few levels.

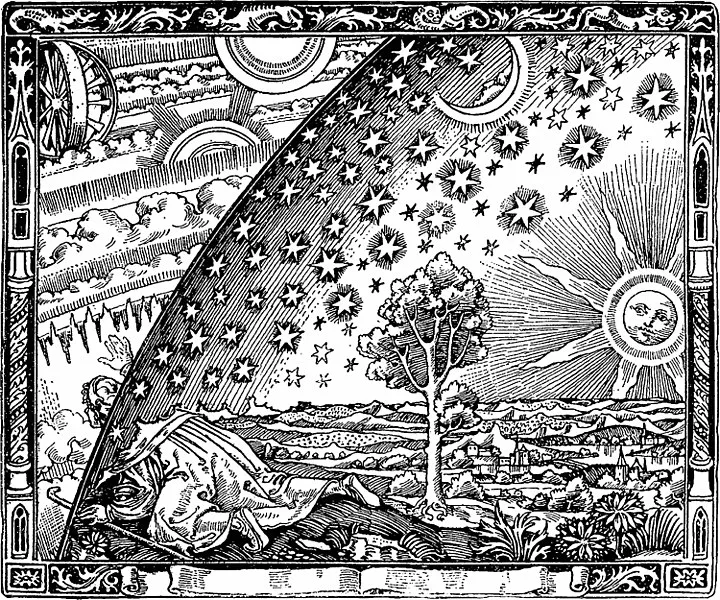

Depictions of a flat earth under a literal dome of stars, like the Flammarion Engraving depicted here (unknown artist) are fairly common in Medieval Europe. They seem, however, to be merely a common and stylish artistic embellishment from the time period. And, honestly, they do look really cool. Texts from the time that discuss the shape of the world essentially universally consider it round, however, so illustrations like this or the exterior of Heironymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights must be considered fanciful. (Which should be clear to anyone who has ever looked at a Bosch painting for more than a couple of seconds.) [Image source]

The historical is far from the only level on which I dislike Occam's Razor, however. More importantly, any effort to simplify science makes me immediately suspicious. The world is messy, difficult, and problematic, and so is science. Efforts to use Occam's Razor to cut the world down to an elegant core of truth end up making that core untrue by forcing so many lies of omission onto it- all those weird, messy bits the Razor is cutting off? Those are as integral to the truth as the shiny bits at the center. Of course, some simplification is ultimately necessary- a scientific theory which tries to be just as complex as the world it describes would be unwieldy to the point of uselessness. It's a difficult and important balancing act between the accuracy of a theory and it having enough simplicity to be useful. Generally, though, I'm going to advocate for more complexity in our understanding rather than less.

There's also the genuine risk that using Occam's Razor can cause real damage. There's an idea called Hickam's Dictum in medicine that exists in direct conflict to Occam's Razor. While Occam's Razor might cause a doctor to look for the simplest explanation for a patient's symptoms, Hickam's Dictum states that "A man can have as many diseases as he damn well pleases." This goes fairly well for research science as well- anthropogenic climate change, for example, isn't caused merely by car exhaust, or coal plants- instead it's caused by those, and by construction emissions, and by cow farts, and by our destruction of natural carbon sequestration processes, and by a long, long list of other factors. It's far from a simple explanation, but it is by far the best one we have.

All that being said, please, please don't take this as me telling you to favor more complicated scientific theories or to disdain simpler ones. I want to make it very clear that you should favor the theories best supported by empirical evidence and testing. And, in fact, the basic idea of not getting too crazy with the number of assumptions isn't really a bad one- Occam's Razor may be safely used if you polish off the rust a bit. Which is to say, if used as a heuristic or loose guideline, it won't do too much damage. You've just got to remember that often the right answer will require you to extend- and then support with evidence- a huge number of assumptions. To the credit of most scientists (with some prominent and unfortunate exceptions), they seem to understand this quite well, and happily abandon simple theories for more complex ones when needed. Like so many philosophy of science debates and arguments, this one is often most relevant outside the immediate practice of solving scientific problems. Learning when and (more often) when not to use Occam's Razor is just part of learning to be a scientist.

“The aim of science is to seek the simplest explanation of complex facts. We are apt to fall into the error of thinking that the facts are simple because simplicity is the goal of our quest. The guiding motto in the life of every natural philosopher should be “Seek simplicity and distrust it.” – Alfred North Whitehead

Bibliography:

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn

- https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/08/occams-razor/495332/

- http://scienceblogs.com/developingintelligence/2007/05/14/why-the-simplest-theory-is-alm/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hickam%27s_dictum

- https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/fpRN5bg5asJDZTaCj/against-occam-s-razor

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam%27s_razor

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_Galilei

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolaus_Copernicus

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plate_tectonics

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myth_of_the_flat_Earth

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Garden_of_Earthly_Delights